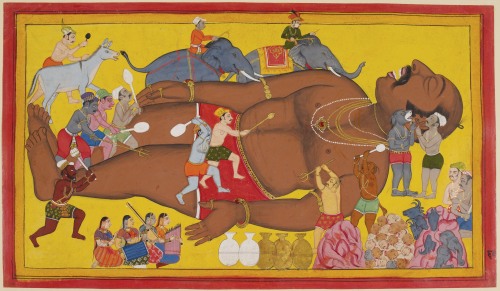

Add. MS 15297(1) f.64a. The demons try to rouse Ravana’s brother, the prostrate giant Kumbhakarna, by hitting him with weapons and clubs and shouting in his ear.

23rd July 2008

The British Library, London

When the British Library realised that the condition of the Mewar manuscript, which they’d had in their possession since 1840, was rapidly deteriorating, it was decided to unbind the series of over 100 illustrations. The 17th century Mewar manuscript had never been exhibited before, and the unbinding presented an opportunity to display these incredibly detailed miniature paintings depicting every scene from the 24,000 verse Ramayana. The British Library invited Tara Arts, the first ‘Asian’ theatre group in Britain, to design the exhibition. Jatinder Verma, artistic director of Tara Arts, talks to Venetia Ansell about the exhibition and the Ramayana today.

It is apt that the British Library should have invited Tara Arts, reputed for their work in connecting cultures, to design this exhibition. Jatinder Verma, one of its founders, is very much a product of multiculturalism. Of Indian-origin, but born in Tanzania and raised in Kenya, he fled to London in the 60s and set up a theatre company in response to racist violence. Since its inception in 1977, Jatinder and his theatre troupe have moved from away from the fringe and are edging into the mainstream. This exhibition of India’s best-loved epic at the British Library could be seen as a parallel coming of age of Indian art in establishment England.

Jatinder, though, is not convinced – “I’ve always said that art is art irrespective of where it comes from.” – and dislikes the ‘Asian art’ tag. And yet he does feel that the focus is moving to the East. That the West is starting to discover an appetite for the literature of the orient as the artistic snobbery that colonialism engendered subsides.

And while it’s true that, “Western museums are products of empire”, Jatinder doesn’t think that the fact the British Library has most of the manuscript is really an Elgin Marble case. Many feel that in a post-colonial era such collections should be returned to their country of origin, but Jatinder believes that the setting for this exhibition is itself a product of today’s British culture – it’s a part of decolonisation. And of course Western museums have far more resources to do this kind of thing than institutions in India. For him, the issue is not where it belongs, but how accessible it is. And the fact that this exhibition is free is hugely important.

But accessibility is much more than just the entry charge – for most people a certain amount of context is needed to make the exhibition comprehensible. Tara Arts designed the exhibition so that the visitor can walk into the world of the Ramayana. There are floral installations, a huge effigy of Ravana, and bright colour coded sections to reflect the “forest world” as Jatinder calls it. He wants the visitor to get a feel for the fauna and flora of the Ramayana, which are often overlooked but form so crucial a part of both the text and these illustrations. Indeed, some of the most beautiful scenes are those of the exiles in the forest (as below), where Ram points out to Sita all the different trees and flowers – many of which are captured with great accuracy by the artists. Jatinder also comments on the wonderful intimacies of the text which are reflected in these drawings – a small section of one painting for instance shows a frightened Sita rush into Ram’s arms at the roar of a lion.

Another important emphasis was the contemporary angle. “This is not a dead book, it’s a living text – it’s important that people understand that.” The Ramayana is, says Jatinder, unique in that it forms a constant dialogue between the text and its modern significance. Its presence in today’s world continually changes the way we look at Valmiki’s epic.

Hindus of course attach great religious significance to the Ramayana – Ram is a god and Sita the ideal wife. But for many Hindus the Ramayana they know is not Valmiki’s (the Sanskrit text upon which the Mewar manuscript is based) but Tulsidas’ Hindi version. “My mother for instance knows the Ramayana inside out but not this version, so I wonder what she makes of this.” As Jatinder says, the war scenes are fairly graphic, with spurting blood and spaghetti strings of entrails all over the place, whereas Tulsidas’ version “has had the blood leeched out of it.” For devout Hindus, too, Valmiki’s text is much less of a homage to Ram than Tulsidas’ more moral ‘Ramacharitmanas’ – Ram here is not explicitly being glorified as the divinity he will become. One of the best things about this exhibition for Jatinder is that it presents a rare opportunity to view and discuss the Ramayana in a non-Hindu context.

There are political elements too which keep the Ramayana current. For instance, Jatinder points out the subtext of the different versions of the Ramayana – that of North Indian colonisation of the South. If you take the portrayal of Ravana for instance you go from one extreme in Tulsidas, where he is an out and out baddie, to the Tamil Kamba Ramanaya where Ravana is in love with Sita, and deals with her honourably. Valmiki’s ambivalent portrayal is somewhere in the middle. And the Ramayana hasn’t escaped controversy in the modern era either – with the Babri Masjid and more recently the Rama Setu, both of which stir up huge emotion in India.

But if the Ramayana is a living text it is perhaps most importantly because it is kept alive artistically as well as religiously and politically. There are hundreds of Ramayanas – almost as many as there are Indians in India jokes Jatinder – and more being produced every day. The exhibition brings this out by displaying many of the artistic representations the epic has inspired, from wayang kulit (Javanese shadow puppet theatre) to MF Hussain (India’s best known living artist). Bollywood film posters attest to the popularity of the Ramayana as entertainment in India even now. For Jatinder all these new interpretations and spin offs continue the conversation between the text and its living avatar. “The key feature of a classic is that it’s indestructible”. A classic is not affected by either time of the artistic progeny which it spawns. “The Ramayana can sustain all interpretations.”

Jatinder intends to work more with Sanskrit texts and talks of doing Kalidasa’s Shakuntala. He accepts though that it would be a huge challenge not only to convey the mixture of prose and poetry which is so hard to do in English but also to present the relationship between the sexes. For Jatinder, it’s not enough to ‘modernise’ the text and bring it in line with contemporary sensibilities. He wants to produce a play which an audience will receive in the same way Kalidasa’s audience would have received it. “I don’t want to bring the classic down to my audience, I want the audience to come up to the classic.” But he admits that it will be difficult to do this in Britain where the concepts of sexuality and sensuality are blurred. “For instance in India you have the saree – a sensual garment which reveals as much as it covers.” In England we have the bikini.

‘The Ramayana: Love and Valour in India’s Great Epic’ is on at the Pearson Gallery in The British Library until 14th September 2008

Admission is free

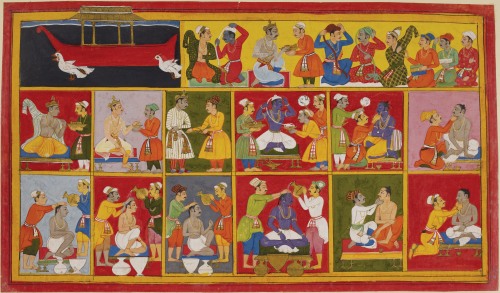

Add. MS 15297(1) f.200a. Rama and the exiles have returned home and he and his three brothers and helpers prepare themselves for his consecration as king.

All images courtesy of the British Library.