Sita and Hanuman in Ravana’s garden, from the kalamkari 5457A in the V&A’s collection

Kalamkari is probably best known in India for its use in kurtas, saris, pajamas and bedsheets. In the 18th century, it was the British who favoured the use of the block-printed cotton cloth for clothes; now it’s trendy Indian lifestyle stores and social groups who promote it for its traditional techniques and natural dyes. Less well known and certainly less readily available are the hand-painted kalamkari textiles depicting epic and mythical material which were made from the 13th century onwards and spread all along the Coromandel Coast and as far as Japan, where they proved very popular.

Professor Anna L. Dallapiccola, former Professor of Indian Art at the South Asia Institute at Heidelberg, Germany, recently wrote the British Museum’s catalogue of South Indian Paintings and is currently working with the kalamkari collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). Professor Dallapiccola talks to Venetia Ansell about several of these kalamkari canopies and the art that produced them.

19th March 2009

Professor Dallapiccola talks about kalamkari hangings with unreserved enthusiasm. Late last year she came to India for Siyahi’s Mantles of Myth – The Narrative in Indian Textiles and discussed two hangings from the V&A which both depict an entire version of the Ramayana. She wanted to explore “what was deemed to be interesting”: which bits of the story the artists highlighted and which parts they have skipped over. The canopies, both of which date from about the 1880s and originate from coastal Andhra Pradesh, are large (about 2 by 3m) but even so space is limited when you are illustrating events from an epic the size of the Ramayana. “Both devote a lot of space to the Bala [childhood] Kanda [book] with all of its pageant”, says the Professor, while the Kishkinda [the monkeys’ kingdom] Kanda is almost entirely omitted, and the Aranya [forest] Kanda makes only a guest appearance. Neither includes the controversial ending in which Rama throws his wife out after their return to Ayodhya. Professor Dallapiccola has seen that only once, in a Sri Lankan kalamkari, “but there it is complicated by regional myths.”

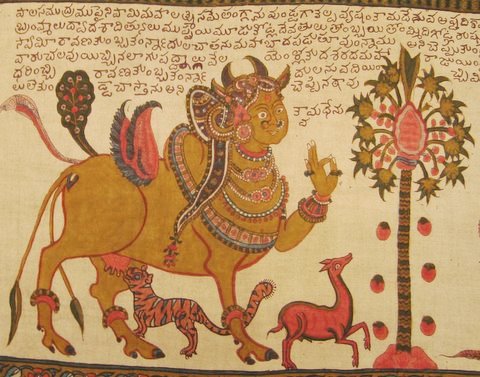

It is not clear what exactly these enormous canopies were used for, but there are “extensive Telugu captions” on the Andhra ones which suggest that they may have been displayed to an audience while a narrator went through each scene of the story. (See image above of a Chirala Ramayana scene, Kamadhenu and the parijata tree, with particularly lengthy notes.) They were commissioned by temples and were probably used to decorate temporary pandals for festivals, although the Professor admits that “it is very difficult to know for certain”.

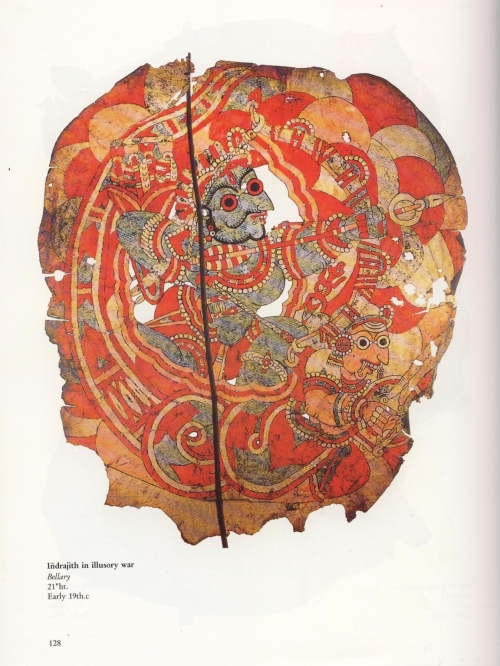

The hangings consist of simple pieces of unlined cloth sewn together. They are not designed to be durable especially in a climate like India’s. Many of the kalamkari temple hangings from Tamil Nadu have seen such heavy use that they are in a terrible state. One of the best preserved is a piece from Chirala, Andhra Pradesh, signed and dated by the artist, which was bought almost immediately by the then Director of the Indian Museum in 1883 and so never actually used. If there are hangings still housed in temples, the Professor has not seen them and suspects that almost all the extant ones are now in private collections or museums.

The art itself though has not died out, thanks to a post-Independence effort by art activists to set up a government kalamkari training centre in Sri Kalahasti, Andhra Pradesh. One of the best living artists, Gurappa Shetty, made what Professor Dallapiccola calls an “absolutely extraordinary” kalamkari canopy depicting the life of Jesus. The canopy was later bought by the V&A.

The representation of Christ is presumably fairly new, but the pre-twentieth century kalamkari artists did not limit themselves to the Ramayana, they also worked on Mahabharata versions as well as regional Telugu literature. The Professor describes some Tamil kalamkari hangings which focus on a particular temple, such as Srirangam, and illustrate the events from that temple’s mahatmya [devotional Sanskrit text glorifying the local deity] on the border.

It may not be possible to see these canopies in their original temple settings, but there are several museums in both India and abroad that house them. In India, the Calico Textile Museum of Ahmedabad is probably the best bet. In London, the British Museum has a few and the V&A itself has about 20 in total. Professor Dallapiccola, who is currently writing the V&A kalamkari catalogue, recommends the V&A. You must make an appointment as the canopies are not on general display, but the museum is apparently extremely helpful and keen to organise special viewings for those who are interested.

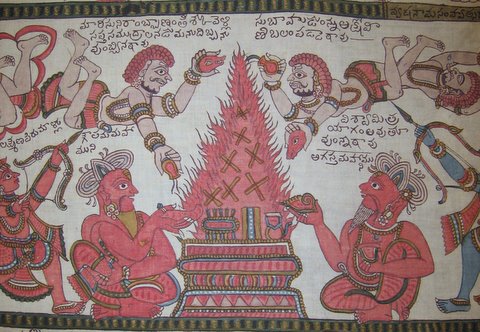

Subahu and Maricha pollute the rishis’ sacrifice

All images courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum