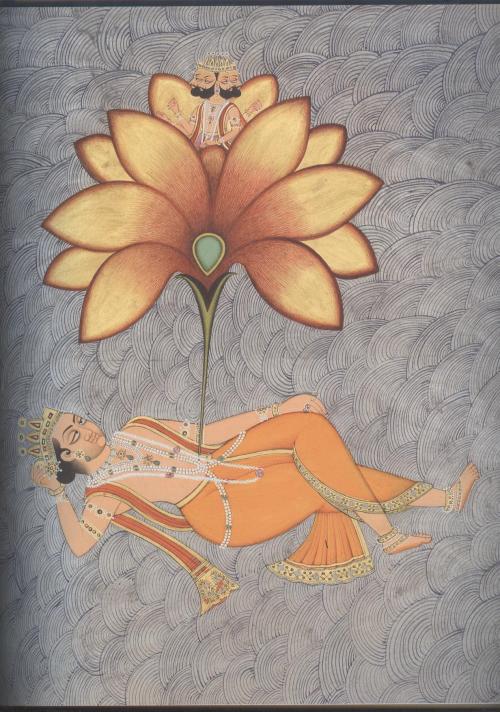

Brahma, springing out of a lotus which had all of a sudden grown out of Vishnu’s navel, promptly lost himself in the flower’s stalk and petals and spent two hundred years trying to find a way out. The lotus is a complicated thing and deserves the rigorous study of a scholarly monograph not a few hundred words in a blog post. Nevertheless, since any description of śarad, or indeed the whole cycle of seasons, would be incomplete without the lotus, queen of all Indian flowers, this article aims to convey something of the lotus and its close cousin the water lily. It has been split into three parts to avoid blog-post overstretch:

– Description in śarad and botanical names (this post)

– Lotuses

Śarad is the season for lotuses and water lilies. Lotuses and water lilies infuse the autumnal breeze with their fragrance – which is said to enthrall even the gods – and lend it its coolness. During the rains, the plants sink under the waters of the lakes and ponds in which they live, avoiding the turmoil and muck. In the Haṃsasandeśa, it is grief at the absence of her lover the swan that causes the lotus pond to withdraw into herself – swans holiday in Mount Kailāsa, avoiding the rain, for the duration of the monsoon.

The personified Śarad has eyes made of the blue petals of the nīlotpala (blue water lily), her face is the blooming kamala (pink lotus) and kumudas (white water lilies) form her smile. This is all standard fare. Men and women have lotus-feet, lotus-hands and lotus-faces. Lotus- or water-lily-eyed are such common epithets – with the blue water lily being the favourite – that with reference to women it comes to mean simply ‘pretty’. Sita Sings the Blues, an amusing and beautifully drawn animated film by Nina Paley based on the Rāmāyaṇa, satirises this tendency by substituting lotuses for most of Sita’s limbs at one point.

दिवसकरमयूखैर्बोध्यमानं प्रभाते

वरयुवतिमुखाभं पङ्कजं जृम्भते ऽद्य।

कुमुदमपि गते ऽस्तं लीयते चन्द्रबिम्बे

हसितमिव वधूनां प्रोषितेषु प्रियेषु॥

divasa-kara-mayūkhair bodhyamānam prabhāte

vara-yuvati-mukh’-ābhaṃ paṅkajaṃ jṛmbhate ‘dya |

kumudam api gate ‘staṃ mlāyate candra-bimbe

hasitam iva vadhūnāṃ proṣiteṣu priyeṣu ||

In this season, the padma opened at dawn by the sun’s rays unfolds with the glow of a beautiful young woman’s face. So too the kumuda withers as the orb of the moon sets, just as women’s smiles fade when their lovers are abroad.

3.23 Ṛtusaṃhāra – Kālidāsa

Thus the lotus blooms at dawn and the water lily at night. However much truth there is in this, and there is certainly some, it is universally accepted in literature to the extent that both the sun and the moon have many synonyms that mean ‘friend/relative/lord of the lotus/water lily’ respectively.

Botanical Names

The Amarakośa lists almost 40 names of lotuses and water lilies. A quick page flip through Monier Williams’ and Apte’s dictionaries throws up at several more. Most of these names have a wide variety of uses. Padma and its variants can also mean an army formation, a female elephant and the number one thousand billion. Very often, the same word can be used to mean the sārasa or Indian crane, which is understandable for the many names that mean ‘born/growing in water/mud’ (ambhoja, sarasija, paṅkaja etc and of course sārasa itself) but more puzzling for words such as rājīva and aravinda unless we assume that the words for lotus and crane became so interchangeable that almost every words that means lotus could also mean crane. The names that are not connected to the idea of lotuses and water lilies growing in water or mud often have interesting etymologies. A comprehensive study of all of these names, their synonyms, their many meanings and their derivations, would be very welcome.

Both Apte and Monier Williams identify some of the many lotuses and water lilies they list but confusion reigns especially because the term ‘lotus’ is often used as a catch-all phrase for lotuses and water lilies. The Pharmacographia Indica lists under “lotus” a range of botanical names several of which are in fact water lilies, a fact seemingly recognised by the authors who identify the last, Nymphaea esculenta, as “the esculent white water-lily”.

All of the lotuses listed below, where identified, are identified by one of three names: Nelumbium speciosum, Nymphaea nelumbo or Nelumbo nucifera. This last is in fact a modern replacement for the first two terms. All three terms refer to the same plant, which we shall for convenience sake call Nelumbo nucifera. Monier Williams himself warns that the padma is “often confounded with the water-lily or Nymphaea alba” but both he and Apte themselves at times succumb to the general confusion. They classify several blue water lilies, such as the puṣkara, as blue lotuses. As Nelumbo nucifera has no blue variety there can therefore be no blue lotuses, only blue water lilies, unless either the Nelumbo nucifera identification is wrong or the blue variety has now disappeared. The Amarakośa lists puṣkara, along with several others generally thought to be blue water lilies, in the general list of lotus names but more importantly it does not note a blue variety of lotuses, only a red and white variety. We can then assume that any reference to a ‘blue lotus’, in Monier Williams and Apte or elsewhere, should in fact be recognised as a blue water lily. The Nelumbo nucifera is described in Pandanus as:

A large aquatic plant, large round leaves up to 90cm in diameter, solitary large fragrant flowers of pink or reddish colour, globose fruits, grows all over India in ponds up to 1800m elevation

Pandanus lists its names in other languages as follows:

– Prakrit – padama, pauma, pamha, poma, pomma

– Hindi – kamal, kaṃval

– Bengali – padma, sveta padma, kamal

– Tamil – tāmarai, centāmarai

– Malayalam – tāmara, veṇtāmara, centāmara

– English – Lotus, Sacred lotus, Indian lotus, Chinese water-lily

The water lilies are more diverse. There are several plants in question and it is not clear which of the blue and white ones the Sanskrit names refer to – or whether they are referring to more than one of each colour. The red variety, the Nymphaea rubra, though is unambiguous.

- Nymphaea alba: A white lotus, known as the European White Waterlily, White Lotus, or Nenuphar; according to Apte this is the kumuda but it doesn’t seem to be found in India.

- Nymphaea lotus: Another white lotus, known as the Tiger Lotus, White lotus or Egyptian White Water-lily. Monier Williams says this is the kahlāra.

- Nymphaea esculenta: A white edible (hence ‘esculenta’) lotus; Monier Williams lists this as the kumuda.

- Nymphaea pubescens: Yet another white lily, this time native to India and South East Asia and known, fetchingly, as the Hairy water lily because of its hairy leaves and stems. This may well be the same as the Nymphaea esculenta.

- Nymphaea stellata: According to Apte this is the aravinda. Again this is native to India and South East India and seems to be the blue variety of water lily.

- Nymphyaea cyanea: Presumably, given the name, a blue variety again; Monier Williams says this is the nīlotpala.

- Nymphaea caerulea: Also known as the Blue Egyptian waterlily or sacred blue lily, it originated from Egypt but is now found in India. It seems to have a pink form as well as the blue.

- Nymphaea rubra: According to MW, this is the raktakumuda.

- Nymphaea nouchali: According to Pandanus this is the kumuda or Indian water lily, known as kanvāl and kokka in Hindi; veḷḷāmpal and allittāmarai in Tamil; āmpal in Malayalam. Pandanus describes it as: “A perennial aquatic herb with short, roundish tuberous rhizome, leaves floating, pelate, flowers large, floating, solitary, variable in colour from white to red, fruits spongy seeded berries.”