Anyone who has ever witnessed the intensity of an early monsoon storm will understand why the word for rain (varṣa in Sanskrit) has come to mean ‘year’ in many Indian languages. The annual arrival of the rains, the season primarily known by the feminine form varṣā, is by far the most dramatic and important meteorological event of the year, and the most eagerly awaited.

Varṣā traditionally spans the months of Nabhas and Nabhasya – nabhas means mist, clouds or sky – or Śrāvaṇa and Bhādra, and thus starts today, 23rd July. In fact India has not one but two monsoons: the first comes from the South-West and tends to hit land in May or June and then make its way North (and East) and a second North-East monsoon follows towards the end of the year. So Kerala is usually in full swing by mid June while Delhi still steams; Chennai tends to get no rain until the cyclone season in December. The monsoon therefore tends to be subject to what corporatese calls ‘scope creep’ – as we see in the Rāmāyaṇa where varṣā has four rather than two months – and it often includes the months of Āṣāḍha and Āśvina (which otherwise belong to the seasons that precede and follow varṣā respectively)

In the Ṛg Veda, the raincloud Parjanya is accorded the full trappings of divine might alongside the other Vedic gods for his procreative power. He brings the life-generating rain either in the form of a furious, raging bull terrorising the earth, or as a cow accompanied by three ‘voices’ of lightning, thunder and rain, his udder-clouds dispensing the longed-for liquid. The hymns ask him to bring rain, but not too much. An excess of rain is just as destructive as its lack. One popular idea expressed in these hymns is that the sun sucks up water throughout the year – and particularly in grīṣma – and the monsoon is the result of sun overflowing. This idea is picked up on in the Rāmāyaṇa:

नवमासधृतं गर्भं भास्करस्य गभस्तिभिः।

पीत्वा रसं समुद्राणां द्यौः प्रसूते रसायनम्॥

Nava-māsa-dhṛtaṃ garbhaṃ bhāskarasya gabasthibhiḥ |

Pītvā rasaṃ samudrāṇāṃ dyauḥ prasūte ras’-āyanam ||

For nine months, the sky drank the ocean’s water, sucking it up through the sun’s rays, and now gives birth to a liquid offspring, the elixir of life.

Rāmāyaṇa, 4.27.3 – Vālmīki

In other respects though, the Rāmāyaṇa’s perspective on the rains – and that of much subsequent poetry – is very different from the Vedic celebration of Parjanya. Rāma has just defeated Valin but because the monsoon is now underway their expedition to find Sītā is temporarily stalled. Retreating to a mountain top with Lakṣmaṇa, Rāma grieves the months away. Varṣā here is the season when all kinds of travel – military as well as merchant – ceases and it is thus the time that men return home and stay put, for a month or two at least. Marooned in their villages and often their houses, people – lovers – enjoy each other oblivious to the storms outside. In the Meghadūta, possibly the most famous poem set in this season, the cloud that bears the yakṣa’s message is welcomed by anxiously waiting wives as he travels north; soon their husbands will return. It is thus especially cruel that Rāma – and indeed the yakṣa who sends the cloud in the Meghadūta – is separated from his wife in this season of all seasons. His descriptions of the rains are unusual and beautiful but also, for him, terrible: he sees Sītā in the hot tears of the burning earth and the lightning that flashes against the dark clouds, and the rains represent the waves of grief that batter him.

By contrast, a storm out of season in the fifth act of the Mṛcchakaṭika sets the scene perfectly for the lovers’ nocturnal meeting. Vasantasenā, glorious as an abhisārikā (a woman who goes to meet her lover), braves the rain and thunder of the night to arrive at Cārudatta’s house soaked through and, as one character notes, bathetically shattering the wet-sari scene, with her feet and ankles covered in mud from the journey. The climactic meeting is prepared for by a string of verses at times startlingly beautiful, punctured by the banter of the servants: the world slumbers, its lotus-eyes closed; the sky, liquefied by Indra’s thunderbolt, seems to be pouring down; the lightning is the slippery gold chain on Indra’s elephant, Airavata who forms the formidable clouds.

एते हि विद्युद्गणबद्धकक्षा गजा इवान्योन्यमभिद्रवन्तः।

शक्राज्ञया वारिधराः गां रूप्यरज्ज्वेव समुद्धरन्ति॥

Ete hi vidyud-guṇa-baddha-kakṣā gajā iv’ ānyonyam abhidravantaḥ |

Śakr’-ājnayā vāri-dharāḥ sadhārā gāṃ rūpya-rajjveva samuddharanti ||

Like elephants these clouds, streaming rain, bound about their girths with chains of lightning and charging against each other, seem to be uprooting the earth on Indra’s orders with silvery ropes.

5.21 Mṛcchakaṭika of Śudraka

At the end of the act, Cārudatta takes Vasantasenā into his house leaving us with a final description, this time of the sound of the rains – or rather the rain, rather than the more normal theatre of the thunder:

तालीषु तारं विटपेषु मन्द्रं शिलासु रूक्षं सलिलेषु चण्डम्।

संगीतवीणा इव ताड्यमानास्तालानुसारेण पतन्ति धाराः॥

tālīṣu tāraṃ viṭapeṣu mandraṃ śilāsu rūkṣaṃ salileṣu caṇḍam |

saṃgīta-vīṇā iva tāḍyamānās tālā-‘nusāreṇa patanti dhārāḥ ||

A high-pitched plink upon the tāla leaves, a murmuring patter upon the branches, a harsh clatter upon the rocks and a violent crash upon water – the rain falls, keeping the beat, like vīṇās in a concert.

5.52 Mṛcchakaṭika of Śudraka

The great natural beauty of the season inspires fantastic descriptions elsewhere too, often of great drama: the monsoon’s arrival as a king in full paraphernalia, or a maddened elephant in rut. One poet has a more subtle verse:

स्थलीभूमिर्निर्यन्नवकतृणरोमाञ्चनिचय-

प्रपञ्चैः प्रोन्मीलत्कुटजकलिकार्जृम्भितशतैः।

घनारम्भे प्रेयस्युपगिरि गलन्निर्झरजल-

प्रणालप्रस्वेदैः कमपि मृदुभावं प्रथयति॥

Sthalī-bhūmir niryan-navaka-trna-romānca-nicaya-

prapancaiḥ pronmīlat-kutaja-kalikājṛmbhita-śataiḥ |

Ghana-ārambhe preyasy upagiri galan-nirjhara-jala-

praṇāla-prasvedaiḥ kamapi mṛdu-bhāvaṃ prathayati ||

Atop a mountain, the earth, revealing a body bristling with goosebumps from top to toe in the sprouting grass and yawning all the while with thousands of just-opening kuṭaja buds, betrays a certain tender thrill towards her lover, the monsoon, with the sweat that trickles down in the form of the coursing waterfalls.

Second verse in the ‘Varṣa-ārambha’ section of the Saduktikarṇāmṛtam

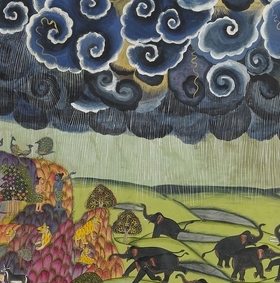

Clouds play a starring role. The very fact that the word ‘cloud’ has 16 synonyms in the Amarakośa – and many more variants thereof – where English makes do with, well, pretty much just cloud bar a couple of Latin terms used by geographers, gives us some idea of the importance these sun-shielding bringers of rain are accorded. In poetry, they inspire the greatest flights of fantasy. The magnificent multiplicity of hues that clouds assume, especially the deep angry blues of clouds that arrive towards the end of an overly hot day capture the poets’ imagination. These clouds are the colour of crushed kohl, a wet buffalo’s belly or a newly-delivered woman’s breasts.

Clouds can assume all manner of weird and wonderful forms. The Meghadūta has a shape-shifting cloud which becomes at various stages Krishna’s peacock feather, a breast, an emerald forming the centre of a pearl necklace, one of the celestial elephants that stands in each quarter of the sky, mud freshly churned up by Shiva’s bull, Vishnu’s foot poised to take its three strides to defeat Bali, Bālarama’s black robe, and a soft stairway to heaven. Clouds are watchmen for the sleeping Viṣṇu, or a search party in pursuit of the villain grīṣma who did so many terrible things, leaving the earth a scorched wreck. One cloud, with lightning as his torch, roams the world searching for any separated lovers who are still living. And often the clouds are drunkards, full to the brim and charging around dangerously, ready at any moment to spew out their heavy loads.

The hymn to Parjanya talks of the joy that he brings, an idea later poets explore in great detail – and none better than Kālidāsa who describes the effect the cloud has on everything he encounters on his journey north. Leaving aside the joy of the reunited lovers, there is a more primitive sort of exhileration that seems to grip the birds and the beasts as well as the trees and even the mountains and the sky itself, which dances for joy. Peacocks, the creature most associated with the rains, look eagerly to the clouds for their cue to start dancing; one of several synonyms for the bird is ‘he who dances to the sound of the clouds’ (megha-nāda-anulāsī). Cātaka birds (Cucculus melanoleucus), who live on raindrops, petition the clouds to release their streams of water. The white balākas – a type of crane – too have an intimate relationship with the clouds, flying alongside them in elegant strung out garlands. Upon the ground, frogs begin their din of croaks, while other animals react with a more general sense of euphoria. Fireflies – kha-dyota/jyoti in Sanskrit, ‘light of the sky’ – fill the humid night air and by day there are the indragopas (literally ‘those protected by Indra’), a distinct red insect that features often in poetry of this season. Trees too respond to the rain, fruiting and flowering; thunder alone brings out the flowers of the kadamba.

Beyond the varṣā of the poetic imagination, the details woven into many of these verses evoke the rains with great precision. A storm is heralded by the first few, uneven drop of rain. Several refer to the smell that the earth gives off just after rain, and so too the softness of the wind after a deluge – in contrast to the great bombast with which it blows to herald the oncoming rain. One poet talks of the grass pushing up earthen umbrellas as it sprouts. Another contrasts the confusion that the rain brings with the shiny newness of a world freshly washed. One poet, eschewing the grand and romantic, gives us a more humdrum description of the mud and the rain.

देवे वर्षत्यशनपवनव्यापृता वह्नि-हेतोर्गेहाद्गेहं फलकनिचितैः सेतुभिः पङ्कभीताः।

नीध्रप्रान्तानविरलजलान्पाणिभिस्ताडयित्वा शूर्पच्छत्रस्थगितशिरसो योषितः संचरन्ति॥

Deve varṣaty aśana-pavana-vyāpṛtā vahni-hetor gehād gehaṃ phalaka-nicitaiḥ setubhiḥ paṅka-bhītāḥ |

Nīdhra-prāntān avirala-jalān pāṇibhis tāḍayitvā śūrpac-chatra-sthagita-śiraso yoṣitaḥ saṃcaranti ||

When god rains, women, busy trying to fight the raging wind, covering their heads with an umbrella made of a cane winnowing basket, grabbing hold of the edges of roofs with their hands and treading on makeshift bridges of piles of planks for fear of the mud, go from house to house in search of a fire.

Verse 59 in the Varṣā section of the Subhāṣitaratnabhāṇḍāgāram

Apologies for the transliteration errors in this post – problems with importing certain letters into WordPress.

A very interesting post with nice quotes.

btw, I don’t have any difficulty importing unicode davanagari (or roman) into WordPress. I couldn’t see any transliteration errors in this post either.

I was looking for the stanza starting from: “Garbham dadhati arkyam” (The sun impregnates), which describes the hydrologic cycle – from evaporation to water flowing back to the seas through cloud formation, raindrop formation, rainfall and sutface flow. Some has attributed this the Maghdootam of Kalidasa but I could not find the stanza there. Can anyone please help in finding this stanza?

thanks. It is very informative

It is an indicator to understand the background of the poetry/poetic part and the nature involved in it. I refer the same in my paper also,

Regards

Puttu

Thanks Thanks Thanks……………….

can i get all data in hindi

I want it written in Sanskrit

I am collecting Poems / slokas / literary verses in Tamil.

I welcome all such recitals in all languages and faiths irrespective of religions.

I firmly believe that Group Prayer can certainly bring a good Shower for the benefit of Human Race anywhere in this world; hence this request.

Thanks and regards

G.Yayathi

Hi, can u pls let me know if u know rishi shinger shloka for rains?

sanskrit itself means pure,why not the text in sanskrit, it will help and bring attention.there may be also hindi or sanskrit but also sanskrit.just a propasal,thanks,sapnil

very good knowledge giving. We are in hydropower generation and diversifying in other fields of power generation. want quotes in sanskrit to permanent use with our logo.kindly forward. kdpdubey,dy manager corporate communication ,thdc india limited. dubey.kapildeo@gmail.com 9411106928

do you have a poem about this thing? upload it?

I am sure to look at rain with a different perspective now onwards.

Super and easy to understand

Interesting

i am looking for a beautiful word in sanskrit that means Dance of the Rains or RainDance …. is there such a word?